A Pictorial Biography of Gareth Vaughan Jones

by

Margaret Siriol Colley

From a lecture given to the Oxford Ukrainian Society May 11th 2006

Author of More Than a Grain of Truth and A Manchukuo Incident,

|

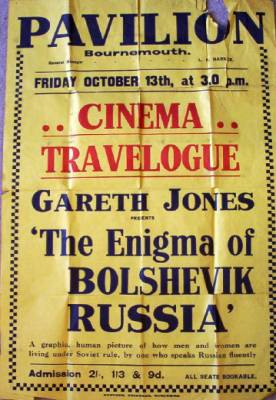

70 years ago Gareth Jones my uncle, gave a series of lectures entitled The Enigma of Bolshevik Russia. He spoke in Newcastle. Manchester Birmingham, Bournemouth, Nottingham and Belfast. He spoke to the Rotarians in Dublin referring to the suppression of Religion in the Soviet Union. The chairman compared Gareth’s oratory with Charles Parnell and John Dillon, the Irish Nationalist of Westminster fame in the 19th century. |

|

|||

Gareth

Richard Vaughan Jones

|

|

|||

John

Hughes

|

|

|||

|

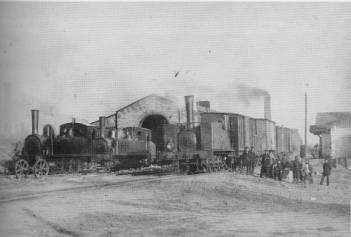

Railway engines at the works in Hughesovka in the 1880’s |

|

|||

Annie Gwen Jones with Arthur Hughes and his familyIn 1889 Mrs Annie Gwen Jones, Gareth’s mother, was appointed tutor to the children of Arthur Hughes the grandchildren of John Hughes and she remained with the family for three years leaving suddenly with them on account of cholera riots in the town.

|

|

|||

Gareth with his mother, Annie Gwen JonesAs a child in the early nineteen hundreds, Gareth Jones heard many tales from his mother, Mrs Annie Gwen Jones about her experiences in Ukraine. She taught him until the age of seven. It was the stories of her youthful experiences that instilled in Gareth Jones a desire to visit the country where his mother had spent three memorable years.

|

|

|||

|

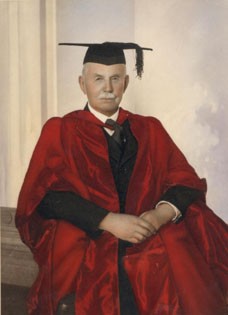

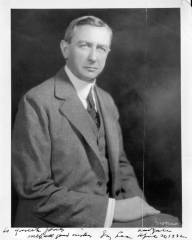

Major Edgar Jones, Gareth's father

All knew my grandfather as the Major. He was commander in chief of the Glamorgan Garrison during the First World War and the name major was a courtesy title which remained with him ever afterwards. He was headmaster of Barry County School for Boys for nearly 35 years

|

|

|||

|

Aberystwyth College Gareth attended his father, Edgar Jones’ school in Barry South, Wales, after which he studied at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, and the University of Strasbourg..

|

|

|||

|

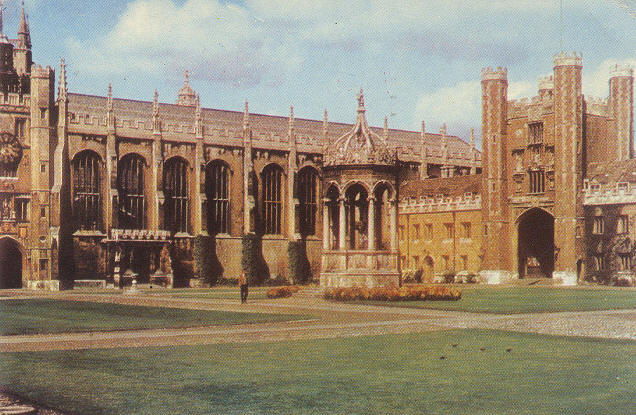

Trinity College He won an exhibition Scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge At Trinity he excelled himself gaining First Class honours in Russian which he spoke fluently, and he was fluent also in German and French |

|

|||

|

Rt. Hon David Lloyd George Surprisingly enough, despite Gareth’s excellent degree, he found it difficult to gain employment due to the economic Depression of the period, but a close friend of his father, Dr Thomas Jones, who had been David Lloyd George’s Private secretary in the Great War introduced him to the Former Prime Minister of Great Britain and Gareth joined the staff of the great Welshman for more than a year as Foreign Affairs Adviser

|

|

|||

Joseph StalinThis post card was sent to his mother. In the summer of 1930 Gareth made his first visit to the Soviet Union. His previous visit had been thwarted due to diplomatic relations having been severed after the Arcos Espionage Affair in 1927. Instead he signed on as a stoker in a coal carrying ship and made his way to Riga to perfect his spoken Russian. Finally in 1930 he was able to make his pilgrimage to the town of Hughesovka about which his mother had spoken so frequently. But he did not stay long.

|

|

|||

|

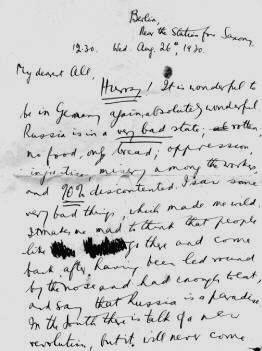

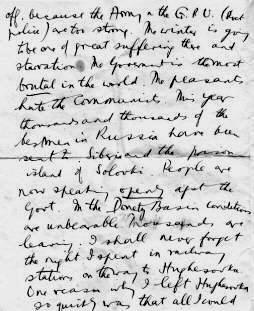

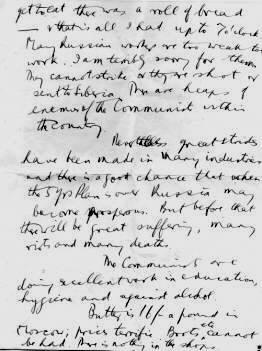

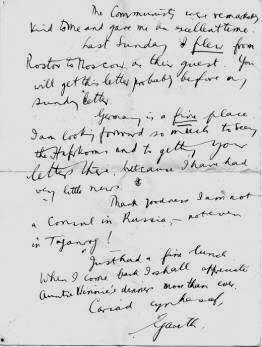

Berlin letter Gareth said little about his experiences while in the Soviet Union but as soon as he reached Berlin he sent this letter home. In Berlin, Near the Station for Saxony,12.30. Wed. Aug. 26th, 1930: My dearest All Hurray! It is wonderful to be in Germany again, absolutely wonderful. Russia is in a very bad state; rotten, no food, only bread; oppression, injustice, misery among the workers and 90% discontented. I saw some very bad things, which made me mad to think that people like [deleted name] go there and come back, after having been led round by the nose and had enough to eat, and say that Russia is a paradise. In the South there is talk of a new revolution, but it will never come off |

|

|||

|

because the Army and the O.G.P.U. (Soviet Police) are too strong. The winter is going to be one of great suffering there and there is starvation. The government is the most brutal in the world. The peasants hate the Communists. This year thousands and thousands of the best men in Russia have been sent to Siberia and the prison island of Solovki. People are now speaking openly against the Government. In the Donetz Basin conditions are unbearable. Thousands are leaving. I shall never forget the night I spent in a railway station on the way to Hughesovka. On reason why I left Hughesovka so quickly was that all I could

|

|

|||

|

get to eat was a roll of bread – and that is all I had up to 7 o’clock. Many Russians are too weak to work. I am terribly sorry for them. They cannot strike or they are shot or sent to Siberia. There are heaps of enemies of the Communist within the country. Never the less great strides have been made in many industries and there is a good chance that when the Five-Year Plan is over Russia may become prosperous. But before that there will be great suffering, many riots and many deaths. The Communists are doing excellent work in education, hygiene and against alcohol. Butter is 16/- a pound in Moscow; prices are terrific, boots etc. cannot be had. There is nothing in the shops. |

|

|||

|

The Communists were remarkably kind to me and gave me an excellent time. Last Sunday I flew from Rostov to Moscow as their guest. You will get this letter probably before my Sunday letter. Germany is a fine place. I am looking forward so much to seeing the Haferkorns and getting your letters there, because I have had very little news. Thank goodness I am not a Consul in Russia – not even in Taganrog! Just had a fine lunch. When I come back I shall appreciate Auntie Winnie’s dinner more than ever. Cariad cynhesaf Gareth |

|

|||

London TimesAs soon as Gareth had returned to London he was called to Churt, the country residence of Lloyd George for the weekend. There he met Seebohm Rowntree who had advised Lloyd George on his National Insurance Act of 1911 and Lord Lothian. Lothian introduced Gareth to the editor, Geoffrey Dawson of the Times and three of Gareth’s articles were published in this newspaper entitled the Two Russias. Later five articles were published in the Welsh newspaper, the Western Mail,

|

|

|||

|

In the Western Mail, Gareth concluded with the words “that the success of the Plan ( that is the Five-Year Plan of Collectivization and Industrialisation) would strengthen the hands of the Communists throughout the world. It might make the twentieth century a century of struggle between Capitalism and Communism. |

|

|||

Ivy Lee

|

|

|||

Gareth and Jack Heinz

|

"With knowledge of Russia and the Russian language, it was possible to get off the beaten path, to talk with grimy workers and rough peasants, as well as such leaders as Lenin’s widow and Karl Radek. We visited vast engineering projects and factories, slept on the bug-infested floors of peasants’ huts, shared black bread and cabbage soup with the villagers - in short, got into direct touch with the Russian people in their struggle for existence and were thus able to test their reactions to the Soviet Government’s dramatic moves." |

|||

|

Noted in the diary were the pitiful conditions of the peasants and a typical entry made during their walking tour in the countryside was : "The vice-president of the Kolkhoz came in to say goodnight, and stayed to talk: " There were forty Kulak families in this village." he told them “and we’ve sent them all away. We sent the last man only a month ago. We exiled the entire families of these people because we must dig out the Kulak spirit by the roots! They go to Solovki or Siberia to cut wood, or work on the railways. In six years, when they have justified themselves, they will be allowed to come back. We leave the very old ones, ninety years and over, here, because they are not a danger to the Soviet power. Thus we have liquidated the kulak! " But the next day he came and whispered to them. “It is terrible,” he said, as he shook his head. “We can’t speak or we’ll be sent away. ‘They took away our cows, and now we have only a crust of bread. It’s worse, much, much worse than before the Revolution. But in 1926-27 - those were the fine years! |

|

‘Dizzy with Success' Joseph Stalin leaving the Legislative Hall in Moscow. |

||

|

Gareth visited a German Commune and was told: "They sent the kulaks away from here and it was terrible. We heard in a letter that ninety children died on the way - ninety children from this district. We are all afraid of being sent away as kulaks for political reasons. We had a letter from one, saying they were cutting wood in Siberia. Life was hard and there was not enough to eat. It was forced labour" |

Gareth and Jack Heinzvisited the Dnieperstroi Dam. The photo is taken from a Gareth's slide used for his lectures

|

|||

|

“Get

the women out of the homes” One of the slogans of Soviet Union |

Illustration from Heinz's book. (Soviet News Agency) Farmers’ wives learning to read |

|||

|

Posters brought home by Gareth from the USSR“ "The tractor is in the field. It is the end of the Will of God.” by the artist Cheremnykh. |

“The Road to World Wide October (Revolution) Hoover Plan – Crisis” |

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

“Preparing Resistance to Growing Reaction” By Letkar |

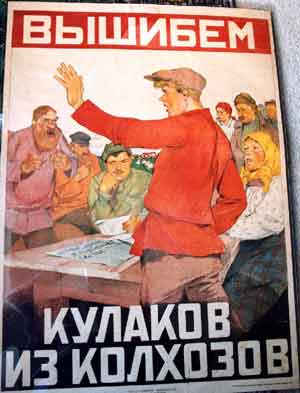

“We will Keep Out Kulaks from the Collective Farms” |

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

As elsewhere the problem of unemployment in America was very great. In January 1932 Gareth wrote to David Lloyd George who inserted the letter into his book The Truth about the Reparations and War Debts ; I had last night a vivid picture of the contrast of the America of yesterday with the America of to-day, when I strolled down the most dazzling part of Broadway. Piccadilly would be a like a Methodist chapel in the country compared with the electric lights and the movies and the dance places there. But right in the centre I saw hundreds and hundreds of poor fellows in single file, some of them in clothes which once were good, all waiting to be handed out two sandwiches, Due to the financial situation in America, Ivy Lee could no longer pay all his staff. Gareth returned to his old ‘chief,’ David Lloyd George in London for another year. Unbeknown to many, during this time Gareth assisted the former Prime Minister to write his War Memoirs researching secret war papers. |

|

|||

|

By September 1932 Academics and Journalists were fully aware of the famine in Ukraine. Gareth wrote two articles which were published in The Western Mail on October 15th and 17th “Will there be Soup” Gareth also wrote in The Western Mail of his reception by Lenin’s widow, Nadezhda Krupskaya in the Commissariat of Education in Moscow on 15 year Anniversary of the October Revolution. |

|

|||

|

He was present in Leipzig the day in January that Adolf Hitler was made Chancellor. On February 23rd Gareth flew with the dictator from Berlin to Frankfurt. This is Gareth’s most famous article. In Hitler’s Aeroplane, Three o’clock Thursday Afternoon, February 23. “If this aeroplane should crash the whole history of Europe would be changed. For a few feet away sits Adolf Hitler, Chancellor of Germany and leader of the most volcanic nationalist awakening which the world has seen."

|

|

|||

|

The flight was to Frankfurt to attend the Frankfurt rally where Hitler was given a tumultuous welcome. Then Hitler comes. Pandemonium! Twenty-five thousand people jump to their feet. Twenty-five thousand bands are outstretched. The “Heil, Hitler,” shout is overwhelming. The people are drunk with nationalism. It is hysteria. Hitler steps forward. Two adjutants take off his brown coat. There is a hush. Hitler begins in a calm, deep voice, which gets louder and louder, higher and higher.

|

|

|||

Gareth visits Soviet Union and Ukraine March 1933Soviet famine 1933“There is no Bread … We are waiting for death."

In the old times,” the old man bewailed, “that was one pure mass of gold. Now it is all weeds.” The old Ukrainian went on moaning: “In the old times we had horses and cows and pigs and chickens. Now we are dying of hunger. In the old days we fed the world. Now they have taken all we had away from us and we have nothing. In the old days I should have bade you welcome, and given you as my guest chickens and eggs and milk and fine, white bread. Now we have no bread in the house. They are killing us.” In one of the peasant’s cottages in which I stayed we slept nine in the room. It was pitiful to see that two out of the three children had swollen stomachs. All there was to eat in the hut was a very dirty watery soup, with a slice or two of potato, which all the family and in the family I included myself, ate from a common bowl with wooden spoons. Fear of death loomed over the cottage, for they had not enough potatoes to last until the next crop. When I shared my white bread and butter and cheese one of the peasant women said, “Now I have eaten such wonderful things I can die happy.” I set forth again further towards the south and heard the villagers say, “We are waiting for death.” Press release by Gareth [given to H.R.Knickerbocker, March 29th 1933.] On Gareth’s return to Berlin he gave a press release after his tramp through Ukraine which was published in the New York Evening Post in full by H. R. Knickerbocker and also in many British newspapers including the Manchester Guardian, the London Evening Standard, the Yorkshire Post and even the Nottingham Guardian. Everywhere was the cry, ‘There is no bread. We are dying.’ This cry came from every part of Russia, from the Volga,. Siberia, White Russia, the North Caucasus, Central Asia. I tramped through the Black Earth region because that was once the richest agricultural farmland in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening. In the train a Communist denied ‘to me that there was a famine. [on his way to Ukraine] I flung a crust of bread which I had been eating from my own supply into a spittoon. A peasant fellow-passenger fished it out and ravenously ate it. I threw an orange peel into the spittoon and the peasant again grabbed it and devoured it. The Communist subsided. I stayed overnight in a village where there used to be 200 oxen and where there now are six. The peasants were eating the cattle fodder and had only a month’s supply left. They told me that many had already died of hunger. Two soldiers came to arrest a thief. They warned me against travel by night as there were too many ‘starving’ desperate men. Response from Duranty on March 31st 1933 in New York Times Two days later, March 31st 1933 in the New York Times, Walter Duranty, a U.S. correspondent, and 1932 Pulitzer Prize Winner, long in Soviet good graces, denied there was famine and promptly presented a rebuttal, but it was a rebuttal of classic Orwellian ‘doublespeak’: But - to put it brutally - you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs, and the Bolshevist leaders are just as indifferent to the casualties that may be involved in their drive toward socialization as any General during the World War.[One] . . . Since I talked with Mr. Jones I have made exhaustive inquiries about this alleged famine situation. . . . There is serious food shortage throughout the country with occasional cases of well-managed state or collective farms. The big cities and the army are adequately supplied with food. There is no actual starvation or death from starvation, but there is widespread is mortality from diseases due to malnutrition. . . . Gareth’s Reply To Walter Duranty The New York Times on May 13th, 1933 then printed a reply from ‘Mr. Jones’ to Walter Duranty’s article of March 31st in which Gareth, in a letter to the newspaper said he stood by his statement that the Soviet Union was suffering from a severe famine. The Soviet censors had turned the journalists into masters of euphemism and understatement and hence they gave “famine” the polite name of “food shortage” and “starving to death” was softened to read as “widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition”. Countering Walter Duranty’s rebuttal in the New York Times, Gareth Jones congratulated the Soviet Foreign Office on its skill in concealing the true situation in the U. S. S. R.. “Moscow is not Russia, and the sight of well-fed people there tends to hide the real Russia.” Quote from Eugene Lyons’ Assignment in Utopia. Another Moscow correspondent, Eugene Lyons in his book Assignment in Utopiaii, written after his disillusionment with the Great Soviet Socialist Experiment, described how Gareth Jones’ portrayal of the shocking situation in Soviet Russia and Ukraine was publicly denied by the Moscow Foreign Correspondents; Persuaded by the head censor in the Bolshevik News Agency, Comrade Umansky, the correspondents were placed in position where they more or less had to condemn Gareth Jones as a liar. To quote Lyons: “Throwing down Jones was as unpleasant a chore as fell to any of us in years of juggling facts to please dictatorial regimes - but throw him down we did, unanimously and in almost identical formulas of equivocation. Poor Gareth Jones must have been the most surprised human being alive when the facts he so painstakingly garnered from our mouths were snowed under by our denials.” Gareth’s many articles Despite the adverse criticism, Gareth Jones on his return wrote many articles about the plight of the Soviet peasants and in particular that of the Ukrainians in British, American, French and German newspapers to tell the world of the famine and terror that he had seen on his travels. Even he narrowly escaped arrest at a small railway station in Ukraine. In the Daily Express of April 5th 1933 Gareth wrote of his journey to Ukraine: I piled my rucksack with many loaves of white bread, with butter, cheese, meat and chocolate which I had bought with foreign currency at the Torgsin stores. I arrived at the station in Moscow from which the trains leave for the south, picked my way through the dirty peasants lying sleeping on the floor and in a few minutes found myself it the hard class compartment of the slowest train which leaves Moscow for Kharkoff . . . In every little station the train stops, and during one of these halts a man comes up to me and whispers to me in German: “Tell them in England that we are starving, and that we are getting swollen.” . . . The young Communist says to me: “Be careful. The Ukrainians are desperate.” But I get out of the train, which rattles on to Kharkoff, leaving me alone in snow. Everywhere Gareth heard the tragic cry: “We have no bread.” Curiously after April 20th 1933 no more articles of Gareth’s articles were published. I feel from this time we were seeing the policy of appeasement by the British Establishment in the 30’s following Hitler becoming Chancellor and the rise of Nazism. Bolshevist Russia was needed as an ally Interview with Maxim Litvinoff and Gareth is accused by him of espionage. Before he left Gareth interviewed the Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs Maxim Litvinov and he sent David Lloyd George a copy of the report. Gareth achieved the dignity of being a marked man on the black list of the O.G.P.U. and was barred from entering the Soviet Union. There was a long list of crimes which he had committed under his name in the secret police file in Moscow and espionage was said to be among them. Malcolm Muggeridge In February 1934 Malcolm Muggeridge with whom Gareth had met and corresponded published his book Winter in Moscow. In it Gareth was characterised in a chapter entitled Ash-Blond Incorruptible as an ash-blond, bearded, pipe-smoking, wine-drinking elderly, Mr. Wilfred Pye. Muggeridge quoted the passage from Gareth’s article whereby a starving peasant darted at the discarded orange peel in the train. ii Assignment in Utopia by Eugene Lyons. George G. Harrap, 1937 Chapter XV, The Press Corps Conceals a Famine Page 577. |

There is no bread. We are waiting for death |

|||

|

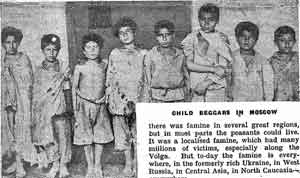

Child Beggars in Moscow |

||||

|

Peasants lying in a Moscow street hoping for food. |

||||

|

Homeless boys in Moscow |

||||

|

Factory workers |

||||

|

Joseph Stalin |

||||

|

The Shock Troop |

||||

|

Commissar Maxim Litvinov |

||||

|

School Children |

||||

|

Soviet

famine 1921-1922 There are few authentic pictures of the genocide-famine, the Holodomor. This one that was circulated in 1933 has since been found to be that of the 1921-22 famine in Ukraine. I was shown this picture and so at the age of eight was made aware of the famine in Ukraine. |

|

|||

|

Gareth with Randolph Hearst at St Donat’s Castle During the following year of 1933, Gareth wrote very little about international affairs, possibly due to this vindictive treatment, but he did write some delightful articles about rural Wales and her home industries for The Western Mail. These were published in a small book after his death, In Search of News - a small book worthy of republishing. In June 1934 Gareth had a most interesting interview with William Randolph Hearst. Hearst spoke of Britain ‘Welshing’ on her debts as there was still controversy over the repayment of War Debts by Britain. Gareth persuaded him to qualify the statement to which he said , “’Welshing on a debt’ is a phrase devised by Englishmen to gratify the vanities and prejudices of Englishmen.” |

|

|||

|

St Simeon, California Unable to return to the Soviet Union; and aware that Japan was an enigmatic problem, the Gareth Jones decided to undertake a “Round the World Fact Finding Tour” and in particular to study Japan’s intentions of colonial expansion in the Far East. At the end of October, 1934 he left Britain bound first for the USA. During his three months stay he visited Wales, Wisconsin, where he interviewed Frank Lloyd Wright. He spent New Years day at Hearst’s Ranch San Simeon in California and in January 1935 sailed from San Francisco for Japan via Hawaii. He wrote more as articles for Hearst syndicate following the murder of Sergei Kirov and describing what he had seen in 1933. |

|

|||

|

Far East Tour During the six weeks in Japan Gareth interviewed a number of military and political leaders including the former War Minister, General Araki Sadao. Japan, short of raw materials had a policy of territorial expansion and in the early thirties Araki had had designs to ‘strike North’ into Siberia and the Soviet Union though later Japan’s plans were to ‘strike South’. Leaving Tokyo Gareth toured the Far East enquiring as he travelled about the political situation in relation to Japan. Of historical note, he arrived in the Philippines two days after Roosevelt had granted the islands Independence. He also journeyed on and visited the Dutch East Indies, Singapore, Siam, French Indo-China and Hong Kong. He travelled on his own through the hinterland of Mainland China in bandit country following a route that Peter Fleming described in his book One’s Company. Eventually Gareth reached Peking before he embarked on his intended destination to Manchukuo, the Japanese colony so named by them in 1932 after the Mukden Incident. |

|

|||

|

In Peking Gareth was invited by Baron von Plessen to accompany him and Dr Herbert Mueller to attend the court of the Mongolian princes and to meet the leader of the Mongols, Prince Teh Wang. Exploring further into Inner Mongolia with Dr Mueller, in the car, loaned to them by the Wostwag Trading Company. The Wostwag organisation was a cover organisation for the NKVD the Soviet Secret police trading in furs. |

|

|||

|

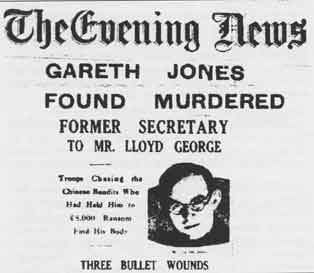

After many hazards, they arrived in the Chinese town, Dolonor on the border of Manchukuo. In Dolonor Japanese troops were massing - between 15,000 to 40,000 - and they noted many armoured vehicles arriving. Apprehended by the Japanese, Gareth and Mueller were advised to take a certain route back to the capital of Chahar, Kalgan. Gareth wrote in the final pages of his diary that there were two ways back - one infested by bad bandits and the other was safe. The following day Gareth and Mueller were captured by Chinese bandits and held for the ransom sum of 100,000 Mexican dollars (£8,000). Mueller was released after two days. Though the ransom was forthcoming, after 16 days in captivity, on the eve of his thirtieth birthday, Gareth, was murdered by these men, disbanded Chinese soldiers, controlled by the local Japanese Military. Gareth’s death made worldwide front-page news. |

|

|||

|

Newspaper Reports

|

|

|||

|

No invasion of China took place in the summer of 1935. Did the Japanese army intend to release Gareth from these bandits thus invading the province of Chahar in north China by peaceful means - The Manchukuo Incident? The Japanese were renowned for engineering incidents, but on this occasion their planned action was foiled by Gareth’s death untimely, but mysterious death. Did the Chinese authorities wish to thwart an invasion of Inner Mongolia by the Japanese ? Did the Soviets collude in this act? Two years later China was invaded by the Japanese culminating in the infamous ‘Rape of Nanking’.xxiv xxiv Margaret Siriol Colley, Gareth Jones, A Manchukuo Incident, Published by Nigel Colley, 2001.

|

|

A small book was published of some of his articles after Gareth's death, In Search of News. The proceeds from the sales went towards a memorial scholarship which is still awarded today. |

||

|

Obituary The Berliner Tageblatt’s highly honourable Editor-in-Chief, Paul Scheffer wrote Gareth’s obituary on August 17th, 1935, in his newspaper with an oblique reference to Walter Duranty who was an amputee and the New York Times The number of journalists with his {Gareth Jones} initiative and style is nowadays, throughout the world, quickly falling, and for this reason the tragic death of this splendid man is a particularly big loss. The International Press is abandoning its colours - in some countries more quickly than in others - but it is a fact. Instead of independent minds inspired by genuine feeling, there appear more and more men of routine, crippled journalists of widely different stamp who shoot from behind safe cover, and thereby sacrifice their consciences. The causes of this tendency are many. Today is not the time to speak of them. |

Freedom Forum Memorial, Washington, May 2004. |

|||

|

Gareth’s ashes were brought back to his beloved Wales and they were buried in Merthyr Dyfan Cemetery in Barry. YMA Y GORWEDD LLWCH GARETH JONES MAB ANNWYL EDGAR A GWEN JONES IEITHYDD TEITHIWR CARWR HEDDWCH A LALLWYDD YM MONGOLIA AWST 12 1935 YN 30 MLWYDD OED HE SOUGHT PEACE AND PURSUED IT. |

.

|

|||

|

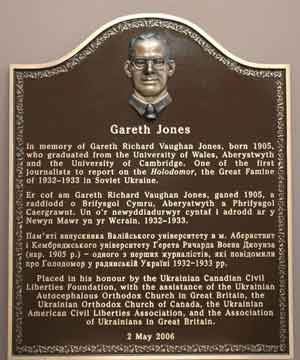

Memorial to Gareth Jones place in the Old College, Aberystwyth University, Wales and contributed to by the Ukrainian Organisations mentioned on the plaque

Gareth Jones was indeed a man who knew too much. |

||||