Members of the Hughes family on a horse drawn sleigh, 1890’s

One winter was exceptionally severe, so severe and so deep was the snow that for two to three weeks we were imprisoned in the house, all communications with the outside world completely broken and the works stopped. Fortunately we had stocked ourselves with provisions in early winter, a wise precaution in such a country. We had visitors staying with us at the time and they were totally unable to leave until the snow was cleared. It was even higher than our windows so that for sometime we saw nothing of the outside world. Still indoor life was not too bad, reading kept us going, cards always for money.

What we had to guard against was sudden snowstorms. They were of frequent occurrence and we had to take great precautions that we should not be caught in them while sledging. It was not at all a rare thing to find peasants who had been overtaken by storms in the Steppes. Several times we returned with some members of our party suffering from frostbite of the nose or cheek. We had to be very cautious indeed. We were on one afternoon on the point, of going out for a sledge drive when we were persuaded not to go as the weather was threatening so we reluctantly stayed at home and it was very fortunate thing that we did for a severe snowstorm came on mere like a whirlwind in nature.

Early next morning 11 bodies were found frozen to death in the Steppes quite close to Hughesovska, including a boy whose mother hailed from Rhymney.

My favourite outdoor pleasure and exercise in winter was skating, but this we could only indulge in the early months before the very cold weather set in. It was a fine scene to see the hundreds of people flitting like swallows over the large frozen reservoir dam (constructed by the company), nor was this exercise confined to weekdays only, Sunday after service in Church was the most popular day for this, indeed for every other form of enjoyment, card playing, circuses, dances, balls, parties of all kinds, riding, boating and hunting. It was on Sunday that the markets and the Bazaar was a scene of great bustle and excitement. Sledging was however as popular and enjoyable outdoor recreation as skating, we often formed parties of 6 or 7 sledges and away we would dash over the Steppes at breakneck pace drawn by Troikas. The Russian Troika consists of 3 horses abreast adorned with bells, the centre horse trots the outsiders gallop, followed almost always by a crowd of the most unsightly wolfish dogs one could ever see. In Russia as in Turkey where dogs act as scavengers it is considered a great crime to kill a dog. They are very numerous indeed, they often seem in a half starved condition and indeed we often thought we were being followed by a pack of wolves.

As the sledge is the conveyance in winter so is the torsi in summer. It more resembles a square plank on wheels than a carriage. It was by no means comfortable on long journeys, or cosy, as there was no support for the back, sitting on his heels was a favourite position with Russian drivers. The severe winter lasts for about 6 or 7 months and often into April and May when an extremely sudden change follows. The antic of snow disappears and the sun bursts out in all its glory, all is covered with an inconceivable thickness of mud, then it is impossible to walk or drive anywhere. Conveyances cling to the mud, people get stuck and only with great difficulty are they extricated.

Suddenly all nature revives, the trees bud and bloom with the most marvellous rapidity and we could almost detect the processes of change. A beautiful eye-soothing greenness covers the plain and then it is that the violets and other flowers spring forth. Indeed it is to me a perfect transformation scene, and all takes place within a few days. But the delight of spring is of far too short a duration, generally a fortnight, it was a cause of congratulation if spring lasted 3 weeks. Summer follows with a heat as intense as the winter was cold.

The winter was the pleasantest season despite the cold; the heat of the summer was simply unbearable. The double padded windows of winter are now reduced to one; the dark blinds are down all day until evening. Flies, mosquitoes, locusts and other unmentionable little brutes abound in thousands; we felt sometimes too languid for anything and would have given much for a whiff of air. Our summer garments were as light as the winter ones were heavy and warm. We kept indoors all day unless it was absolutely necessary to go out, when evening came we went out a little, only then could we endure it. This great heat coupled with the total want of drainage, great dearth of rain, prevalence of dry sand dust gave rise to fevers of all sorts, which greatly damaged our health. The mortality from dysentery especially among little children was simply appalling from 40 - 50. Mothers returned to work in the fields within days after the advent of their little ones.

Sometimes we had no rain for months with the consequence that the works had to close. To amend this state of things a dam was constructed by the company, which supplied the works with water as well as supplying us with a splendid skating and boating ground. The autumn, which is as short as the spring is most cool and pleasant. Then riding was the order of the day and hunting.

I must tell you something about the people. What strikes me immensely is the wide, enormous, unbridged gulf between the upper and lower classes of Russia. Unfortunately there are only two real classes; there is no real middle class, the chief mainstay and backbone of a country. The wellborn Russian despises and spurns the lowborn moujek or peasant and treats him on most occasions more like a dog than a human being. To this day the poor moujek bears the impress of serfdom or slavery in every action and in every word.

It was in 1861 that Alexander II, who was afterwards most foully murdered in 1881, granted emancipation to the serfs who had previous to that been like slaves.

The moujek is a miserable looking individual but well built and tall, he is utterly uneducated, his vocabulary consists of 2-300 words at the most. His arithmetic is extremely elementary, when transacting any business, over which he is very sharp, he reckons up his accounts on an abacus.

The peasant is a fine built man with lovely teeth, his wife is not at all a poor specimen and not bad looking, but all cleanliness is hidden under a most ungainly garb. In winter it is really difficult to distinguish the peasant from his wife, their outdoor garment is so alike. They wear high thick felt boots reaching up to their knees, then a sheepskin cloak the white skin showing with no pretensions to shape or form reaching to the top of the boots. On the head a sheepskin cap covered over with a kerchief or scarf of various or varied colours, this is the costume of both the male and female.

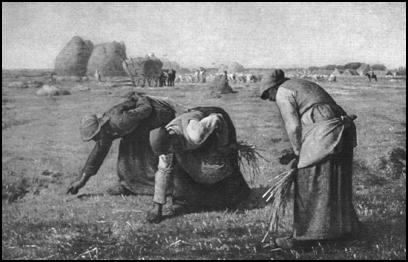

Peasants in the fields.

Their holiday and Sunday apparel is very smart, indeed, the women deck themselves in picturesque costumes of all colours imaginable red, yellow, green and blue prints being the material all mixed up in a most promiscuous manner, a skirt of one colour, a bodice of another bright colour, an apron of another beautifully embroidered as only Russians can embroider with all kinds of threads in all kinds of patterns, the neck adorned with glass beads of all sorts and colours, they wear no hats but tie a coloured kerchief round their heads. They plait their dark hair in many plaits and tie each one with a different coloured ribbon, a married woman with two plaits.

They have no boots on their feet, even pour servants when serving at table never wore boots or shoes and very often when a peasant happens to be the proud possessor of a pair of leather boots, which is very rare indeed, he prizes them so highly that he often walks barefooted and carries his boots on his arm. It is generally a sign that a peasant is better off than his neighbour when he can afford to buy a pair of boots. I liked the peasant moujek, they are very good natured, simple minded and childish.

Their homes are not comfortable, but hovels sometimes dug right down into the ground and built of mud with only a little smoke issuing from a chimney or stove visible. Some were made of wood, but all of one floor, no upstairs and only one or two rooms. Every Russian house whether rich or poor had an icon or an image of Christ or the Virgin Nary or a saint in a top corner of the room, it is before the image that they pray. It is a well-known fact that Russian peasants have no beds but sleep on top of the large stoves, which occupy as a rule 1/3 or 1/4 of the room. In spite of all these drawbacks the Russian peasant has a resigned sort of nature and appears content with his lot.

The Russians are not ‘total abstainers’ nor do they believe in the moderation principle. I have thought it would not be a bad place for the British Temperance Association to start a branch9 though from the onset I could promise them no hope of success. Vodka is the Russian drink par excellence, both rich and poor are addicted to the drinking of it, it is an extremely strong whitish intoxicating spirit distilled from rye containing a high percentage of alcohol. Kvas too is a favourite drink, a kind of light beer made of rye. They drink an enormous mount of tea, in some parts Kiomoso or fermented mare’s milk is partaken especially by those who are afflicted with diseases of the chest. I can only say from personal experience what ever may be its alleged curative properties that mare’s milk is a very refreshing and pleasant drink.

So far I have only told you about one section of the Russian community, now let us look at the other and compare the great difference. The wellborn Russian receives the very best education, at home first of all under the care of governesses and tutors and then at university, men as well as women go, they are well read, artistic and excellent linguists. It is nothing for them to know 4 or even 6 languages besides their own and converse in them fluently. They are lazy and indolent and consider it beneath them to do any manual work. In their fine country mansions their days and evenings are given up to amusement, dancing, cards and music. Still in some respects they are the most accomplished people that one could wish to meet, some of them are the most marvellous musicians. With all their faults, which are numerous and evident, they are most hospitable, lavishing much on their equals and foreigners but their treatment of the peasant was certainly unpardonable.

They are fond of jewellery wearing many rings on their fingers. Both men and women are inveterate smokers holding the cigarette in their much jewelled fingers, the men are most flattering in their attention to the ladies, they take pride in saying pleasant things utterly devoid of meaning, it is their way, extravagant in everything. There are not many rich Russians; most of the noblemen are in the hands of the usurers who have mortgaged their estates to the hilt. It is a shame that in a rich country like Russia that there are so many poor. The mineral wealth of the country is immense but they have neither the will nor the energy nor the money to found or start any new works or manufactures.

There are gangs of robbers and thieves stationed here and there, we had a night watchman whose sole duty, accompanied by his lantern, his dog and his whistle, was to parade around the house each night. The works also had to be guarded and so Mr Hughes obtained the Government’s permission to have some Cossack soldiers at Hugheffka in case of rioting. Mr Hughes had barracks built for them, their pay was very little, practically nothing apart from their food; they were a body of about 100 men. The Cossacks had customs and actions that were marvellous and their wild charges accompanied by weird yells and howls struck terror into us onlookers and forced an impression upon us of a savage and uncivilised race of men.

The Russians have a peculiar mode of address. It is very rarely that you hear their surname. Take for instance John Jones, son of William Jones, the Russians would say Ivan Vasilovich, Anne Jones would Anna Vasilovna the feminine termination. Perhaps the three questions that will interest most people are religion, the Nihilists and the treatment of the Jews.

There is hardly any need for me to tell you who the Nihilists are. I may say that they are not the easy-going peasants but generally made up of students of the University who came from what they call the ranks. Their university training has raised them as they think above their former position and when their university course is over they do not feel inclined to return to their former position or tread their father’s footsteps. The professions are not open to them nor can they ever obtain a high place in the army, all professions and position of high rank are kept exclusively to the upper ranks. We have a band of men and women (which is unjust) discontented with their lot, unable to attain the social position they desire and driven to secret revolt against the existing state of affairs. They form secret societies whose sole object is to rouse and educate the masses of their secret writings and their agents to revolt against the form of Government. They wish to instil into the people a desire for a new condition of things (and rightly so)

Many of the Nihilists are moved by a strong, burning, sincere love for their country and a keen desire to better its conditions. Some however stoop to ignoble and criminal means of carrying out their aims and intentions. Much as one sympathises with their ideals, one cannot sympathise with open assassination like that of Alexander II in 1881 of the dastardly attempt upon the life of the late Czar Alexander III by wrecking his train.

I remember passing over the spot many times, now a Church is built on the spot to commemorate the escape. At first it was thought to have been an accident, but was one of the cleverest plot imaginable. The servant, who in the act of handing him a cup of tea, was killed on the spot as well as the dog at his feet. The Czar himself was quite unhurt though the train was a complete wreck. Whenever the Emperor undertakes a railway Journey the whole route along, which he goes is lined with soldiers at a distance of a few yards. All telegraphic communication is stopped so that traffic is dislocated and the Nihilists cannot communicate to a band in the next town. Every care is taken to keep him and his family from danger.

The peasants used to look on the Czar as a supernatural being, they used to call him ‘The Holy Father”. Unhappily the head that wears the crown is especially true of the Russian Monarch; one hears of so many plots, so many attempts on his life. The Czar, we are told is not as black as he is painted. The Nihilist agitation is fast shaking the social order to its foundations.

I shall relate a tale I was told by a Russian Gentleman of a Nihilist who was caught red-handed trying to shoot the late Emperor when out driving, and though the man was caught in the act, declared that he was not guilty. He said that he belonged to a band of Nihilists who were bent on getting rid of the Emperor. Lots are usually drawn as to who shall carry out the work of the plotters and on this occasion it fell on the accused man, who happened to be the best and surest shot, to shoot the Emperor. He was compelled by orders of the Brotherhood, so set out and waited for his opportunity of firing at the Emperor. He said that he purposely missed his aim (he had never been known to miss before) and so saved the Emperor’s life. He could have shot him if he liked, but he confessed that he could not do it in cold blood. He knew that if he refused the orders of the band he himself would be shot and he knew that Siberia would await him had he perpetrated the deed so he begged for mercy from the court and strange to say obtained it.

Extreme care had to be taken by all of us as to our conversation about Nihilist matters. One day when entering a room where there were several Russian visitors and seeming all to be silent and absorbed I thoughtlessly made the remark: “You all look as if you were hatching a plot against the Emperor” whereupon I was seriously warned to be cautious of my remarks.

Now I come to the punishment of the Nihilists. I believe that Russia (I am not sure about Switzerland) is the only country where hanging has been abolished, but there are tortures worse than death and there are deaths from starvation and cruelty more numerous in Russian prisons then cases of hanging in England. Hanging is considered too mild and too speedy a form of punishment so other methods of torture were invented, the knout and mutilation and disfigurement of the face followed by a journey to one of the poisonous mines of Siberia never to return. In the entire language of civilisation there is no word that conveys an idea of more cruelty, more superhuman suffering than that conveyed by the word Knout. The knout has not been used for a hundred years, but three cases have been known in recent times, to hear the word in Russia is to shudder. When the prescribed number of cuts have been given the victims are taken to hospital where the wounds are dressed with salt and when recovered are taken to Siberia. They start on their awful journey, the prisoners, both men and women, are as a rule attired in a uniform kind of dress which is a long loose great coat of a rough grey cloth. Groups or bands of the convicts are fettered together by chains or rings so as to make it easier for the guards to watch them.

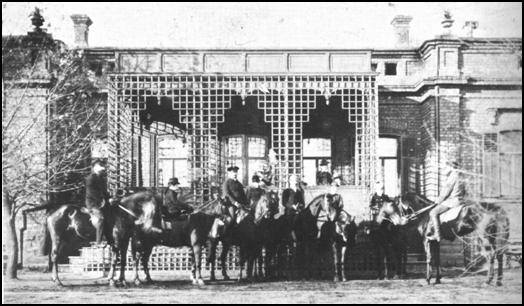

Family gathering outside the Dacha

Every English paper was read through in the head Post Office and then if there was any remark derogatory to the Russian Government the paper then was either confiscated or the paragraph blotted out. Certain books were not allowed into Russia. As an example of the extreme precaution not to allow dissenting bodies into Russia, the last time I crossed the frontier I was not allowed to have a passport without a declaration that I belonged to the State Church (Church of England) (not by me).

Continue on page 6